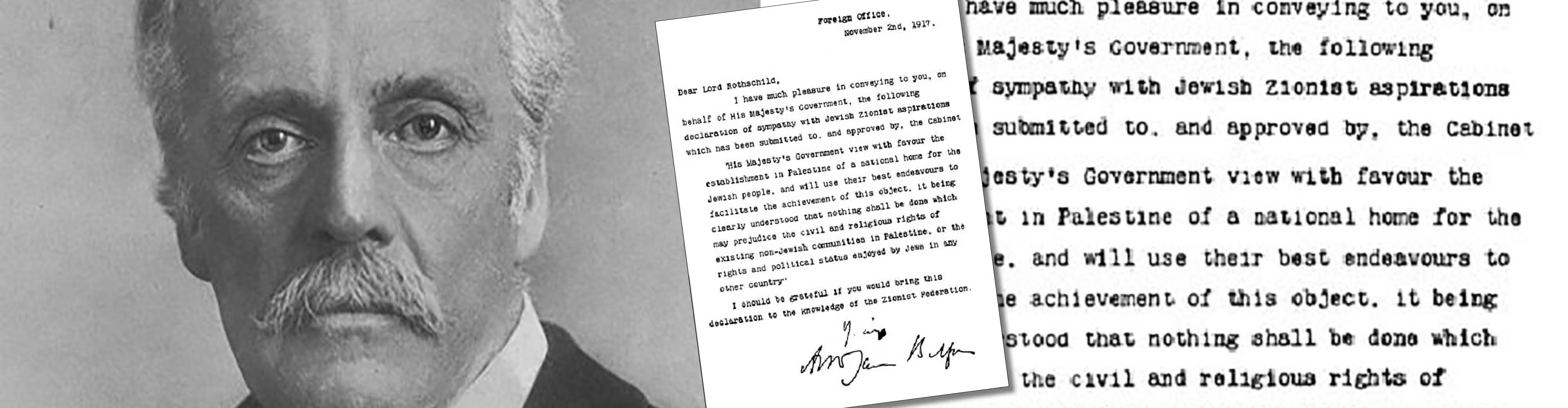

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 was a public statement in which the British government announced its support for “a national home for the Jewish people” in the land of Palestine, at that time a part of the Ottoman Empire. The declaration, included in a letter that was sent from the British government to the Zionist Federation on the 2nd November 1917, states:

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The declaration was made at a time when the tumult of World War I was pushing imperial powers such as France and Britain to consider the futures of various territories around the world, particularly in the Middle East. With this background in mind, historians cite a range of both strategic and ideological reasons for the declaration, including the presence of dedicated Zionists in the British cabinet, as well as the aim of gaining a foothold in the region. In the words of Lord Balfour, “the four great powers are committed to Zionism and Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desire and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land. In my opinion that is right.”1

Aside from the fact that the legitimate right to give the land away was not that of the British, and that the British had already promised the land back (through independence) in the 1915 Hussein-McMahon correspondence, the wording of the document is of particular importance. The ambiguity of the language shows to be constructive for the Zionist project and destructive for the indigenous Palestinian population, whose political rights are crucially left unmentioned. This ambiguity meant that there was leeway in how the British would offer this promise, and the clause regarding the civil rights of the Palestinians has still not been realised until this very day. Importantly, there is no mention of political rights for the native Palestinians of the land, nor was there any consultation with the indigenous inhabitants of the land before this declaration was made.

The Balfour Declaration is significant for various reasons: it meant that one of the chief imperial powers of the day officially lent its support to the Zionist project; it marked the denial of the political rights of the indigenous Palestinians from that same power; and it was officially incorporated into the terms of the British Mandate of Palestine.

For resources on the Balfour Declaration, see:

- David Gilmour, ‘The Unregarded Prophet: Lord Curzon and the Palestine Question’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 25, no. 3 (1996), pp 60-68

- Sahar Huneidi, ‘Was Balfour Policy Reversible? The Colonial Office and Palestine, 1921-23’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 27, no. 2 (1998), pp. 23-41

- Victor Kattan, From Coexistence to Conquest: International Law and the Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1891-1949

- Rashid Khalidi, ‘Introduction: Historical Landmarks in the Hundred Years’ War on Palestine’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 47, no. 185 (2017), pp. 6-17

- Walid Khalidi, ‘Palestine and Palestine Studies: One Century after World War I and the Balfour Declaration’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 44, no. 1 (2014), pp. 137-147

- William Mathew, ‘War-Time Contingency and the Balfour Declaration of 1917: An Improbable Regression’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 40, no. 2 (2011), pp. 26-42

- Bernard Regan, The Balfour Declaration: Empire, the Mandate and Resistance in Palestine

- Edward Said, The Question of Palestine

- Alexander Scholch, ‘Britain in Palestine, 1838-1882: The Roots of the Balfour Policy’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 22, no. 1 (1992), pp. 39-56

Footnotes:

- Said 1980, 16-17